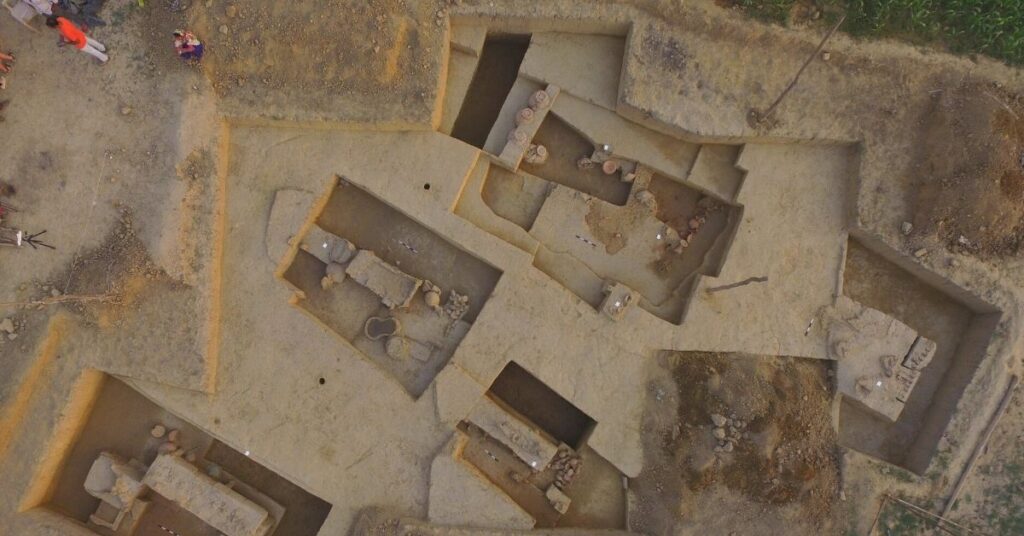

In 2021, archaeologists from Tamil University, led by Dr. K. Rajan, excavated a site in Mayiladumparai, a village in Tamil Nadu’s Krishnagiri district. At a depth of 2.5 meters, they uncovered the remnants of an ancient iron-smelting furnace containing charcoal fragments.

Using Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS), a precise radiocarbon dating method, the team determined the charcoal to be 4,200 years old, dating the furnace’s operation to 2172 BCE. This discovery represents the earliest confirmed evidence of iron production in Tamil Nadu and South India.

The furnace was a simple pit structure lined with clay, designed to withstand high temperatures required for smelting iron ore. Associated finds included iron slag (a byproduct of smelting) and tuyères (clay pipes used to blow air into the furnace to intensify heat). These artifacts confirm systematic iron production, indicating advanced metallurgical knowledge for the period. The site’s stratigraphy showed continuous use from 2172 BCE to around 800 BCE, suggesting ironworking was a sustained practice in the region.

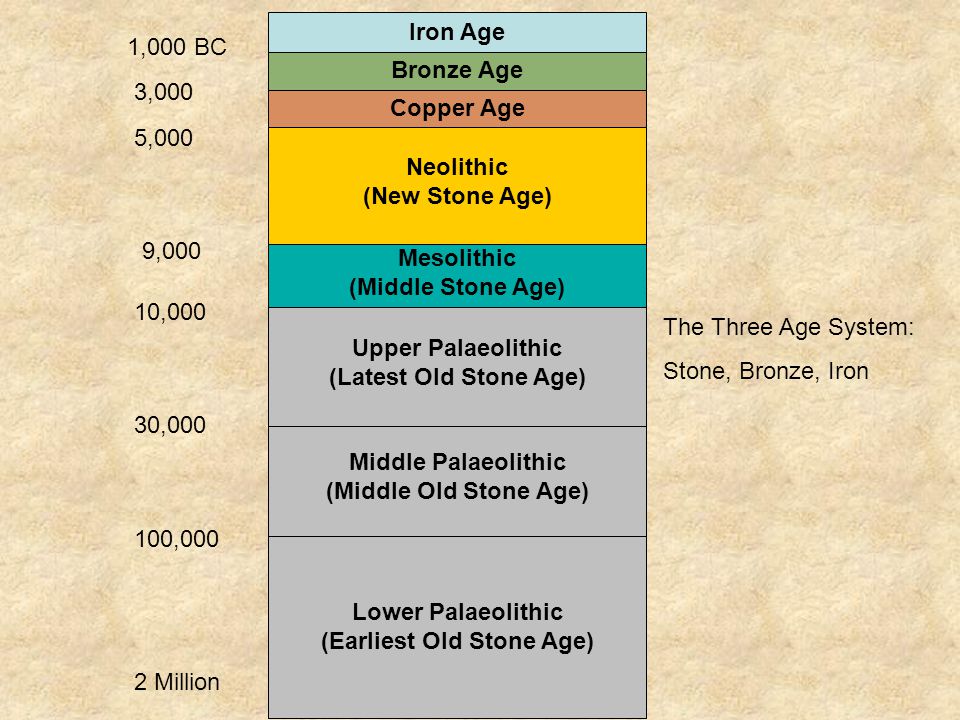

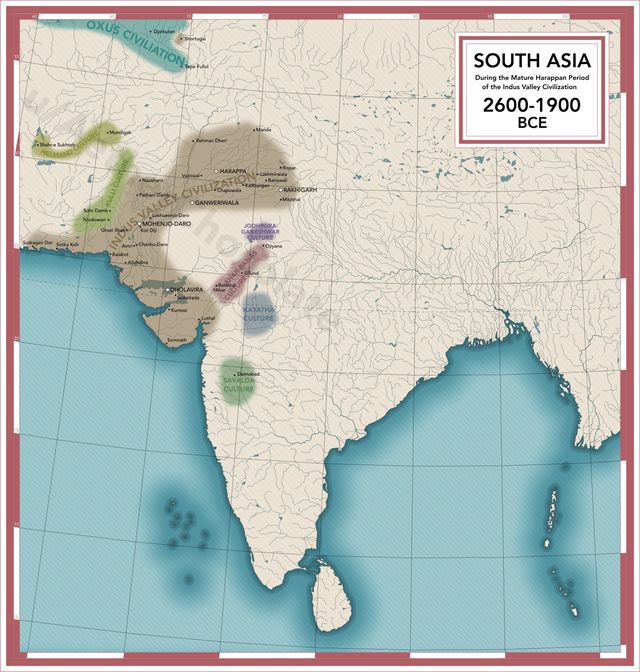

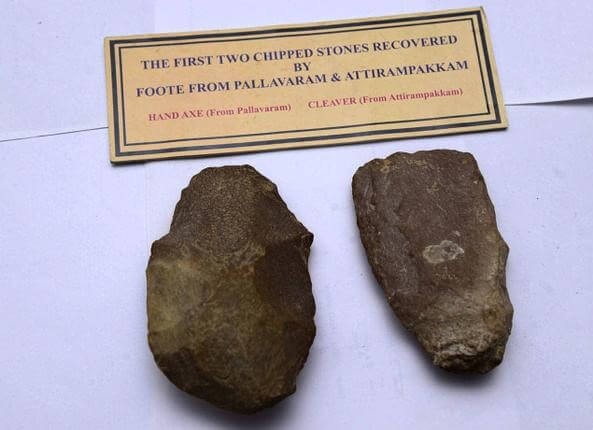

The dating of the Mayiladumparai furnace (2172 BCE) aligns it with the mature phase of the Indus Valley Civilization (2600–1900 BCE), challenging previous assumptions that iron technology in India emerged later in the Gangetic plains (circa 1200–1000 BCE). Crucially, it predates the hypothesized timeline of the “Aryan migrations” (post-1500 BCE), a theory that linked iron technology to Indo-European-speaking groups. This finding undermines the notion that ironworking was introduced to South India via external migrations, suggesting instead indigenous technological development.

The Mayiladumparai site is part of Tamil Nadu’s megalithic culture, characterized by distinct burial practices like urn interments and the use of iron artifacts. Nearby sites, such as Adichanallur (3,800-year-old burials with iron weapons and Tamil-Brahmi-inscribed pottery) and Kodumanal (known for high-carbon steel production and Roman trade links), indicate a regional network of early iron use. These connections suggest that Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age communities were not isolated but part of a broader technological and cultural milieu.

The discovery sparked significant debate among historians and archaeologists. Dr. R. Balakrishnan of Tamil Nadu’s Archaeology Department hailed it as a “paradigm shift,” emphasizing that the findings validate Tamil Nadu’s early technological autonomy. Dr. Vasant Shinde, former director of the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), acknowledged its importance but cautioned against framing it as a “North vs. South” rivalry, stressing the likelihood of interregional exchanges. Initial skepticism about the AMS dating methodology was addressed when peer-reviewed journals, including Archaeological Research in Asia, validated the results.

The findings directly challenged colonial-era historiography, which positioned South India as a peripheral player in India’s civilizational narrative. They also disrupted the Aryan migration theory’s association of iron technology with post-1500 BCE migrations. While some scholars argue for a pan-Indian exchange of metallurgical knowledge, others emphasize the need to recognize regional innovations. The discovery has intensified calls for reexamining institutional biases, as the ASI historically prioritized North Indian excavations, leaving southern sites understudied.

The DMK’s Ironclad Agenda

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), Tamil Nadu’s ruling party, capitalized on the archaeological discoveries at Mayiladumparai to advance its political and cultural agenda. Chief Minister M.K. Stalin, in a high-profile 2023 speech at the ancient burial site of Adichanallur, framed the findings as a symbol of Tamil pride. He declared, “These urns hold not just bones but the pride of a civilization that mastered iron while others lingered in bronze,” positioning Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age as evidence of Dravidian ingenuity and autonomy. This rhetoric was part of a broader strategy to challenge North India-centric historical narratives and assert Tamil identity.

In August 2023, the DMK government launched the Tamil Heritage Mission, allocating ₹1,200 crore ($145 million) to preserve and promote the state’s ancient heritage. Key initiatives under this mission included:

Restoration of Iron Age sites like Kodumanal (known for advanced metallurgy), Adichanallur (famous for urn burials), and Mayiladumparai (the 4,200-year-old iron-smelting site).

A ₹200 crore museum in Chennai, featuring interactive exhibits on Sangam-era metallurgy and trade, alongside smaller regional museums.

Overhauling school curricula to emphasize Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age achievements, removing references to “Aryan contributions” and replacing them with modules on Keezhadi (a 2,600-year-old urban settlement) and Korkai (an ancient port linked to Roman trade).

Dr. R. Balakrishnan, Tamil Nadu’s Cultural Secretary, stated, “This is about dignity. For too long, Delhi’s historians treated us as peripheral. Now, we’re recentering our narrative.”

The DMK leveraged symbolism to amplify its message. During the 2024 Republic Day celebrations, Tamil Nadu’s float showcased a massive replica of an Adichanallur burial urn labeled “4,000 Years of Tamil Genius,” directly contrasting the BJP’s emphasis on North Indian Hindu heritage. On social media, hashtags like #IronAgeTamilNadu and #DravidianDawn trended, juxtaposing images of megalithic artifacts with the BJP’s Ram Temple iconography. These efforts aimed to position Tamil Nadu as a civilizational peer to the Indus Valley and Vedic cultures.

The DMK’s campaign faced backlash from political opponents and scholars. AIADMK leader Edappadi K. Palaniswami criticized the allocation of ₹200 crore for museums amid agrarian distress, asking, “Why spend on museums while farmers struggle?” Archaeologists like Dr. R. Nagaswamy accused the DMK of selective storytelling, noting, “They glorify Tamil autonomy but ignore evidence of pan-Indian trade networks that connected Keezhadi to Gangetic plains.” Critics argued that the party’s focus on “Dravidian exceptionalism” risked fragmenting India’s interconnected historical narrative.

Despite criticism, the DMK’s strategy resonated with Tamil voters. A 2023 poll by Thanthi TV found 74% of Tamil respondents believed their heritage predated the Vedas, reflecting broad support for reclaiming Tamil Nadu’s historical legacy. The government’s emphasis on cultural pride, coupled with tangible investments in heritage infrastructure, solidified its image as a champion of Tamil identity.

Hindutva’s Counterattack—The Indus-Vedic Tightrope

The Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its ideological parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), faced an existential dilemma following the discovery of iron smelting in Tamil Nadu dating to 2172 BCE. The Sangh Parivar, which has long positioned the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) as the cradle of Vedic Hinduism, struggled to reconcile Tamil Nadu’s advanced Iron Age timeline with its narrative of a continuous, Sanskrit-centric civilizational unity. The findings directly challenged the notion that iron technology arrived in India via “Aryan migrations” (post-1500 BCE), forcing the BJP-RSS to recalibrate its historical claims.

To mitigate the political and ideological fallout, RSS-affiliated scholars and BJP leaders deployed several strategies:

RSS ideologue J.K. Bajaj argued that bull figurines at Adichanallur symbolized “proto-Nandi,” linking them to Hindu Shaivism. Archaeologists like Dr. K. Rajan, lead excavator at Mayiladumparai, dismissed this: “There’s no Shiva lingam or Vedic ritual evidence here. These are secular burial artifacts.”

Sangh-backed studies emphasized shared genetic markers (haplogroup R1a) between North and South Indians to suggest a “common Vedic ancestor.” Geneticist Dr. Kumarasamy Thangaraj countered: “These markers predate the Vedic period by millennia. They reflect ancient migrations, not Vedic continuity.”

The BJP-led central government responded by downplaying the findings while amplifying narratives aligned with Hindutva. Union Culture Minister G. Kishan Reddy called all ancient cultures “threads in Bharat’s fabric,” but NCERT’s 2023 textbooks devoted 42 pages to the Indus Valley and only 2 pages to South Indian megaliths. Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M.K. Stalin condemned this as “intellectual colonialism,” accusing the Centre of erasing southern contributions.

Hindutva groups doubled down on excavations in Ayodhya and Kashi to reinforce their narrative of Hindu continuity. In 2023, the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) claimed evidence of a “2,500-year-old temple” beneath Ayodhya’s Babri Masjid, mirroring Tamil Nadu’s emphasis on ancient heritage. Historian Romila Thapar noted: “Both sides weaponize archaeology—one to assert Hindu primacy, the other to reclaim Dravidian pride.”

The BJP-RSS response highlights the tension between ideological narratives and empirical evidence. While the Sangh Parivar seeks to uphold a unified “Hindu civilizational” identity, the Tamil Nadu findings expose the complexity of India’s past. The politicization of archaeology, whether in Ayodhya or Mayiladumparai, underscores a broader struggle to control historical memory in service of contemporary power dynamics.

Archaeology as Soft Power

The discovery of iron smelting in Tamil Nadu dating to 2172 BCE not only reshaped India’s historical narrative but also drew significant attention from global actors, each with their own agendas. China, for instance, seized the opportunity to exploit India’s internal divisions. Leaked directives from China’s Ministry of State Security revealed a deliberate strategy to “amplify India’s historical rifts.” State media outlets like Global Times published articles such as “India’s Iron Age Fault Lines” (2023), drawing parallels between Tamil Nadu’s assertions of cultural autonomy and the unrest in China’s Xinjiang region. The article warned, “Civilizational states fracture when myths dissolve,” subtly suggesting that India’s pluralistic history could be a source of internal discord. This narrative aligns with China’s broader geopolitical strategy to undermine India’s unity by highlighting regional and cultural fault lines.

On the other hand, Western academia played a dual role in the discourse surrounding Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age. Institutions like Harvard University hosted symposia, such as the 2023 event titled “Beyond the Indus: South Asia’s Multiple Dawns,” where scholars used isotopic analysis of artifacts from Kodumanal to link Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age to ancient copper trade networks with Oman. These findings underscored Tamil Nadu’s historical significance as a hub of early metallurgy and trade, challenging the notion of a unidirectional cultural flow from North to South India. However, Western involvement also sparked controversy. The British Museum’s “Tamil Sangam” exhibit, featuring 12 artifacts from Adichanallur loaned under a contentious 1972 agreement, ignited demands for repatriation. Tamil Nadu’s Minister for Youth Welfare and Sports, Udhayanidhi Stalin, criticized the exhibit, stating, “They glorify our artifacts but deny us ownership,” reflecting broader frustrations over colonial-era acquisitions and the lack of restitution.

The diplomatic fallout from these developments was significant. BJP MP Tejasvi Surya accused Western institutions of “reviving colonial Aryan-Dravidian divides,” framing their involvement as an attempt to fragment India’s historical unity. Meanwhile, Tamil activists intensified their efforts to gain international recognition for Tamil Nadu’s heritage, lobbying UNESCO to designate sites like Keeladi and Adichanallur as World Heritage Sites. These efforts were part of a broader push to assert Tamil Nadu’s cultural and historical autonomy on the global stage, often clashing with the BJP’s vision of a unified, Sanskrit-centric Indian identity.

The global reactions to Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age findings highlight the intersection of archaeology, geopolitics, and cultural identity. While Western academia’s research has provided valuable insights into Tamil Nadu’s ancient past, it has also reignited debates about colonial legacies and the ownership of cultural heritage. Similarly, China’s attempts to amplify India’s internal divisions underscore the geopolitical stakes of historical narratives. As Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age continues to capture global attention, it serves as a reminder that history is not just a record of the past but a contested terrain where science, politics, and identity converge.

Vigilantes and Vanishing Artifacts

In Tamil Nadu’s villages, the Iron Age is far from an abstract academic debate—it is a lived reality that shapes identities, livelihoods, and conflicts. In places like Keezhadi, where 2,600-year-old Sangam-era ruins lie scattered across farmlands, local farmers have taken on the role of guardians. R. Mani, a 52-year-old farmer, patrols these ancient sites nightly, driven by a sense of duty to protect his heritage. “Last year, looters stole a hero stone inscribed with my ancestor’s victory,” he recounts, his voice tinged with frustration. The Tamil Nadu Archaeology Department has reported a 45% spike in artifact thefts since 2021, with stolen relics often smuggled to international collectors in Dubai and beyond, where “Tamil antiquities” fetch exorbitant prices on the black market. This surge in thefts has forced villagers to become informal custodians of their history, even as they grapple with the economic pressures of modern agriculture.

The Iron Age debate has also ignited tensions among India’s youth, particularly in academic spaces. At Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), Tamil students clashed with their northern peers in 2023 after a Sangam-era mural was defaced. “They called our history ‘fake’,” said M. Divya, a PhD candidate, reflecting the deep-seated resentment many Tamils feel toward what they perceive as North India’s historical hegemony. A 2023 survey by Hindu-CNN-IBN highlighted this divide: 79% of Tamil youth (aged 18–35) viewed their heritage as “superior,” while 67% of Hindi-belt youth dismissed such claims as “divisive mythmaking.” These statistics underscore the growing cultural polarization between India’s North and South, fueled by competing narratives of history and identity.

Beyond India’s borders, the Iron Age debate has taken on a global dimension. In London, the Tamil Heritage Trust hosted a 2023 exhibit titled “From Megaliths to Metropolis,” drawing connections between ancient Tamil metallurgy and Chennai’s modern IT boom. The exhibit showcased artifacts like iron tools and pottery, alongside digital displays highlighting Tamil Nadu’s technological legacy. Meanwhile, in Silicon Valley, North Indian tech elites organized the “Vedic Futures” conference, featuring panels on “Vedic AI” and “Sanskrit Algorithms” as a counterpoint to Tamil claims of historical primacy. These events reflect how the Iron Age debate has transcended national boundaries, becoming a proxy for broader struggles over cultural representation and pride.

Two Indias, One Past

The debate over Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age is not merely a scholarly quarrel about ancient chronology—it is a high-stakes ideological contest with profound implications for India’s socio-political landscape. This clash over history has morphed into a proxy war for India’s soul, pitting competing visions of national identity against one another. At its core, the dispute asks: Will India embrace its pluralistic past, or will it fracture under the weight of polarized narratives?

The Optimist’s India envisions a future where the nation’s historical narrative is a tapestry woven from diverse regional threads. Museums would juxtapose the Indus Valley’s hydraulic ingenuity (exemplified by Dholavira’s advanced sewer systems) with Tamil Nadu’s metallurgical prowess (showcased in Kodumanal’s iron crucibles). Textbooks would frame India’s past as a collaborative mosaic, where the Gangetic plains’ Vedic hymns coexist with the Sangam era’s Tamil poetry. Such a vision celebrates India’s civilizational diversity, fostering unity through shared pride in localized innovations—a recognition that the subcontinent’s greatness lies in its ability to harmonize.

The Pessimist’s India, however, descends into a fractured reality. Here, the DMK weaponizes Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age legacy to erect ideological walls, framing Dravidian history as inherently separate from—and superior to—North India’s Sanskritized past. Simultaneously, the BJP entrenches a counter-narrative, digging rhetorical moats around Vedic Hinduism as the sole font of Indian identity. In this scenario, citizens become so consumed by competing claims of antiquity that they neglect their shared present—a nation where historical grievance overshadows collective progress, and regional chauvinism eclipses national cohesion.

Dr. Nayanjot Lahiri, a prominent historian at Ashoka University, cautions, “When history is politicized, archaeology becomes a casualty. We risk losing truth to tribalism.” Her warning underscores the peril of reducing millennia of human experience to partisan soundbites. The Iron Age debate exemplifies this danger: as politicians cherry-pick artifacts to fit ideological agendas, nuanced scholarship is sidelined. For instance, the DMK’s emphasis on Tamil “exceptionalism” risks erasing evidence of ancient trade links between South India and the Gangetic plains, while the BJP’s Vedic-centrism dismisses Dravidian innovations as peripheral.

The UNESCO 2023 report amplifies these concerns, labeling Tamil Nadu’s Iron Age sites as “endangered” due to looting and partisan mismanagement. At Keezhadi, villagers now guard 2,600-year-old Sangam-era ruins from smugglers targeting “Tamil antiquities” for Dubai’s black market. Meanwhile, underfunded state archaeologists struggle to balance preservation with political pressures. The report warns that neglect and exploitation of these sites don’t just erase history—they erase the possibility of a shared future.

The Iron Age debate has become a rallying cry for mobilization. The DMK, eyeing a third consecutive term in Tamil Nadu, frames its heritage push as resistance against “Hindi-Hindu hegemony,” appealing to Dravidian pride. Meanwhile, the BJP counters by doubling down on excavations in Ayodhya and Kashi, using claims of “Hindu continuity” to solidify its pan-Indian mandate.

This polarization isn’t confined to India’s borders. In London, the Tamil Heritage Trust’s “Megaliths to Metropolis” exhibit ties ancient metallurgy to Chennai’s tech boom, while Silicon Valley’s “Vedic Futures” conference promotes Sanskrit as the “language of AI.” These global narratives reflect a diaspora divided—a microcosm of India’s internal strife.